In 1956, Flint Hill Preparatory School was founded in Fairfax as a K-12 private school for white students. That same year, U.S. Senator Harry Byrd launched the Massive Resistance in Virginia, legislation enacted to evade Brown v. Board’s mandate for school integration. Senator Byrd is quoted as saying the Massive Resistance was designed “to prevent a single Negro child from entering any white school.” In Fairfax County, the school board gave private school tuition grants to white students fleeing the newly integrated public school system. In 1959, 44 of those grants went to Flint Hill Prep students.

Being straightforward about Flint Hill’s segregational founding is important to Head of School Patrick McHonett. “Acknowledging that part of our history is essential to validating the impact it has had on our students, past and present,” he says. “These are uncomfortable facts, reflective of the time, and not something we should shy away from.”

We need to own where we’ve been in order to recognize how far we’ve come, as well as chart a pathway forward.

–Patrick McHonett, Head of School

Being straightforward about Flint Hill’s segregational founding is important to Head of School Patrick McHonett. “Acknowledging that part of our history is essential to validating the impact it has had on our students, past and present,” he says. “These are uncomfortable facts, reflective of the time, and not something we should shy away from.”

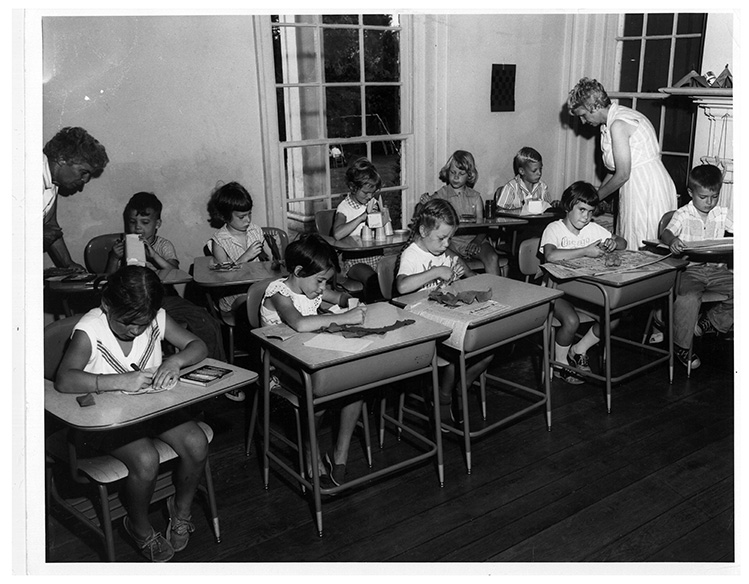

Leading up to Flint Hill Prep’s founding, Northern Virginia was going through a demographic transformation as rural families migrated to the newly developed suburbs at a pace faster than the public schools could keep up with. When Ann Cole Paciulli ’69 came to Flint Hill Prep for 9th grade, her parents were among those frustrated with the overcrowded classrooms and dilapidated public school buildings. “My school was built in 1890, and it was impossible to accommodate everyone,” she says. “I could only go to school for half the day, and there were 40 kids in my class.” Something else that provided momentum for the rise of Flint Hill Prep was the fact that it offered differentiated instruction, which students did not get in public school. It also offered kindergarten. At the time, the earliest children could begin their public school education was 1st grade. Flint Hill Prep was an oasis for white families wanting a better education for their children as well as for those seeking refuge from integration.

Originally, students attended classes in what we now call the Miller House, an estate home Flint Hill Prep founder Don Niklason purchased from Helen Miller. Additional classroom buildings and a gym were added in the early 1960s. Ann remembers her time in those classrooms fondly. “The teachers were so invested in us,” she recalls. “The Niklason family themselves were caring people. They were at every football game, cheering on the players, and getting to know the students in the stands.” As Flint Hill alum Kate Blaszack ’01 writes in her book, Flint Hill School: A History, Don Niklason saw Flint Hill Prep as a business venture that would provide Fairfax residents the excellent private school education he himself had received. Don grew up in Arlington and attended Devitt Preparatory School before going on to the University of Virginia. Kate writes that Don sought to “give other students the opportunities that a good education offers.”

Mia Burton, Director of Institutional Equity and Inclusion (IEI), refrains from using words like “nuanced” or “complex” to describe the school’s founding. The School didn’t admit students of color in those early years, she points out, stating, “Flint Hill functioned as a segregation academy whether that was Don Niklason’s motivation or not.”

“I didn’t know that about Flint Hill when I came here as a freshman,” Ida Guerami ’23 recalls. Ida’s first year at Flint Hill was marked by the arrival of COVID-19, the debut of distance learning, and the racial reckoning ushered in by the summer of 2020. Dear Flint Hill emerged as a student-run social media account, giving voice to the unique challenges faced by students of color on campus. One issue brought up by that account was the School’s perceived silence around its founding. Ida says she scanned the yearbooks to see when students and faculty of color started coming to Flint Hill. She learned that the first Black student enrolled in 1972, and the first Black teacher joined the faculty in 1986. For her senior project, Ida proposed writing lesson plans that shed light on the School’s history for use in Flint Hill classrooms. “There’s so much value in kids knowing about this,” Ida says, adding, “We can’t go back and change it, but we can grow from it, and the only way to do that is through education.”

“A big sense of my activism comes from the fact that I am a first-generation American,” she says. Ida’s grandparents and parents emigrated from Iran during the Iranian Revolution. “Talking about issues in Iran can land you in jail, so speaking openly about social issues here is a right I make sure to exercise.” Her lesson plans were approved by the faculty of the history department and will be taught in 7th and 11th grade classrooms this spring. Ida hopes that by delving into classroom discussions about the School’s founding, students will develop the dexterity to lean into difficult conversations concerning race and American history.

We can’t go back and change it, but we can grow from it, and the only way to do that is through education.

–Ida Guerami ’23

By the early 70s, alum Ann Cole Paciulli ’69 had returned to Flint Hill as a 2nd grade teacher. Though she was delighted to find the same caliber of teachers and quality of education that she enjoyed as a student, the School was barely staying afloat financially. She recalls being paid intermittently and dealing with bounced paychecks. “I would’ve been happy to continue my career at Flint Hill, but I couldn’t live with that uncertainty,” she says. Her tenure lasted just two years. In 1986, the School began construction at its new location on Academic Drive in Oakton, conspicuously spending a quarter of a million dollars to bring the Miller House over to the new campus from Fairfax atop a flatbed truck.

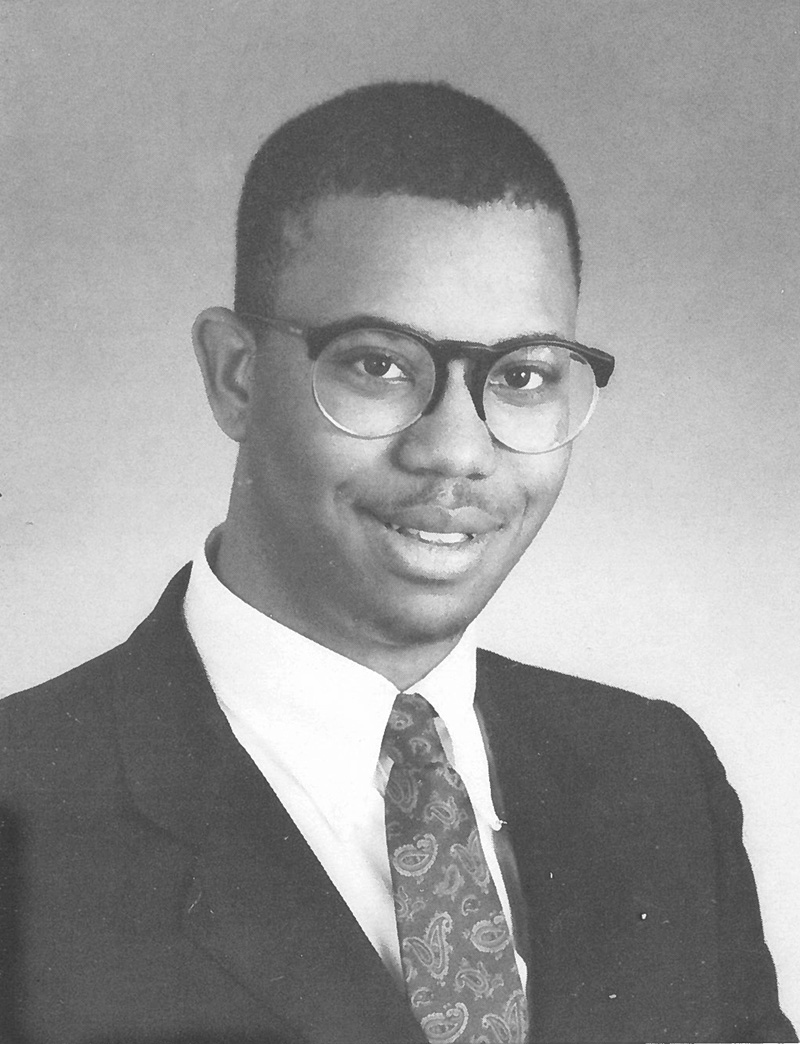

The School’s most radical transformation came in 1990 when Chairman Emeritus John “Til” Hazel successfully reorganized the for-profit Flint Hill Preparatory School into the nonprofit Flint Hill School. “That happened the summer before my senior year,” Jamal Gallow ’91 remembers. He describes the switch to Flint Hill School as night and day, with the arrival of new teachers and new, state-of-the-art facilities.

Having the unique distinction of being both a Falcon and a Husky, Jamal has affection for both iterations of the School. He reminisces about the close-knit community feel of Flint Hill Prep and the fresh energy of the Flint Hill School faculty. He credits both sets of teachers with imparting a true love for learning and helping him navigate his diagnosed learning difference.

“On some level, I didn’t think about the history of the School and its founding,” Jamal recalls. “Representation was not something that was expected then. Plus, to be Black at a PWI (predominantly white institution) you had to not make waves.” He remembers experiencing instances of racism from members of the community, but his parents had prepared him for that and equipped him with how to respond. “That was the way of the world at that time. I didn’t expect Flint Hill to be any different.”

Like Jamal, alumni of color from that time report being one of one in their learning spaces, lacking the benefit that comes with having classmates and teachers who looked like them. Jamal says he contended with a lack of diverse texts to study and a shallow dating pool. “At one time there were just two Black girls in the entire Upper School,” he says.

By the late 90s, Ann had returned again — this time, as a parent. “Same Miller House, different location,” she laughingly recalls. Her daughters learned from teachers like Fred Atwood and Jody Patrick, teachers whom Ann describes as “role models for life.” She found the student population to be refreshingly more diverse. “There were so many different backgrounds represented; it created such a very rich experience for my children,” she says.

Today, 43% of Flint Hill’s student body identify as students of color. Director of IEI Mia Burton asserts, “That doesn’t mean our work is complete. Just because we have racial diversity that reflects our local community doesn’t mean there isn’t more we need to do.” In her role, Mia aims to raise and uphold the quality of each Husky’s lived experience. “Flint Hill hasn’t always seen the benefit of a diverse community, but we know now that the best learning environment is one where students are exposed to different perspectives, learn to approach the unknown with curiosity rather than prejudice, and build an awareness and empathy for the experience of others.”

Jamal has stayed connected to Flint Hill since graduating in 1991. He appreciates hearing about the School’s current IEI efforts, including the recent pivot away from using terms like “Headmaster” and “Founders Day.” “Addressing all of that just was not a conversation that existed 30 years ago,” he says. “I’m proud to see that it exists now.” This fall, alumni of color were invited to gather for an affinity reception in Arlington where they could reconnect, socialize, and talk about their shared experience.

Head of School Patrick McHonett believes these conversations are key to the continued progress of the School. “Frankly, outstanding students we have on campus today would not have been welcome in our original incarnation. We need to own where we’ve been in order to recognize how far we’ve come, as well as chart a pathway forward.” Patrick finds immense value in hearing the endearing and heartwarming stories Falcons tell him about Flint Hill Prep. “They originated the driving spirit and supportive community that our Huskies maintain today.”

“Ultimately,” he says, “the goal is for Ann, Jamal, Ida, and every other member of our community to have a place where they belong and are celebrated for who they are. We’ve always been a caring community. Now, our priorities need to demonstrate what we’ve learned from our past, and how we’ve grown to live our Core Values, to be a just and equitable community for all.”

“Lucky” is how Andrew McKee ’24 describes the feeling of being one of the four history students chosen to…

In 1956, Flint Hill Preparatory School was founded in Fairfax as a K-12 private school for white students. That…

The wisdom and skill of Flint Hill employees don’t just benefit students and colleagues on campus. Our teachers and…

In September, the Flint Hill community was saddened to learn about the loss of former Athletic Director Win Palmer….

From conversing with online chatbots to getting help from Alexa, many of us have already become accustomed to generative…

WANT TO BE IN THE MAGAZINE? To be included in Alumni Class Notes, email the Alumni Office at alumni@flinthill.org with news of a union, birth...

Tradition and Innovation On September 13, Head of School Patrick McHonett led the All-School Gathering, the first assembly of…

From preparing for the large crowd to putting the “spirit” in Spirit Alley, orchestrating Homecoming at Flint Hill is…

This Fall and Winter brought several opportunities for our alumni to get together. From reuniting at Homecoming and our…